Southwood Camp - Cove

May - August 1951

Denis Carrington

The brown manila envelope with a O.H.M.S. stamp on the front arrived at the Carrington household in London's East End borough of Poplar in late April 1951. This was to inform the Carrington's only child Denis, to report on May 17th to No. 9 training regiment R.E. at Cove near Farnborough, Hampshire. A travel warrant and other instructions were also included.

The present day Poplar is a very different place, from the one depicted here in the early fifties. Many of it's industries, buildings, and peoples have changed over the years, indeed the area itself is now known as Tower Hamlets!

I had reached the age of 18 in December1950, and was due to be called up then, but had applied for, and was granted a deferment until May.(It was just as well because the first few weeks of 1951 were to prove to be particularly cold!) This was to enable me to sit a City & Guild examination at the London College of Printing at Stamford Street S.E.1.

My day release to attend the printing college for one day each week was part of my 7 year indentured apprenticeship contract, to become an artisan Lithographer.

It has been said,(by me) that to be a good Lithographic printer, one must be a bit of a mechanical engineer, a bit of a chemist, a bit of an artist, a bit of a mathematician, and on occasions, also a bit of a diplomat!

The college was just a short walk away from the then developing site of the Festival of Britain, and so we were able to watch each week, during our lunch break, its impressive development. This also included a Bailey bridge, built by Sappers of the36 th Army Engineer Regiment, R.E. With assistance from the 25 th & 27 th Engineer Group (T.A.) and the 56 th (London) Armoured Division (T.A.). This bridge which spanned the river at a point near Hungerford rail bridge, enabled visitors easier access to the site from the north bank.

I remember during this time there was a large building opposite the college which housed the Eldorado ice cream factory, which was next to a cleared bomb site, where, during their midday break some of the large number of people they employed, used to play a game of football with as many as 50 or more a side!

Some weeks before my call up papers arrived I had to attend a medical and pre-service interview at a T.A. centre next to the 'George' Hotel Wanstead. This from memory involved having to re-assemble a bicycle pump from its scattered components, a multiple choice literacy and numeracy exam, and an interview with an officer who asked which branch of the services I would like to serve in. I chose the Royal Engineers because I was told this corps was responsible for map printing etc. The last person I saw was the M.O.(Medical Officer) who after the usual perfunctory height, weight, and blood pressure tests, asked me to bend over and touch my toes, (presumably to see if my hat was on straight!), then to put my tongue out for checking, afterwards shining a light into my ear, and if it didn't shine out of the other ear, you were considered O.K! The final indignity was to grab one's naked scrotum with a cold hand while asking you to cough!

So it came as no surprise to be passed A.1 despite having had rheumatic fever since three years old!

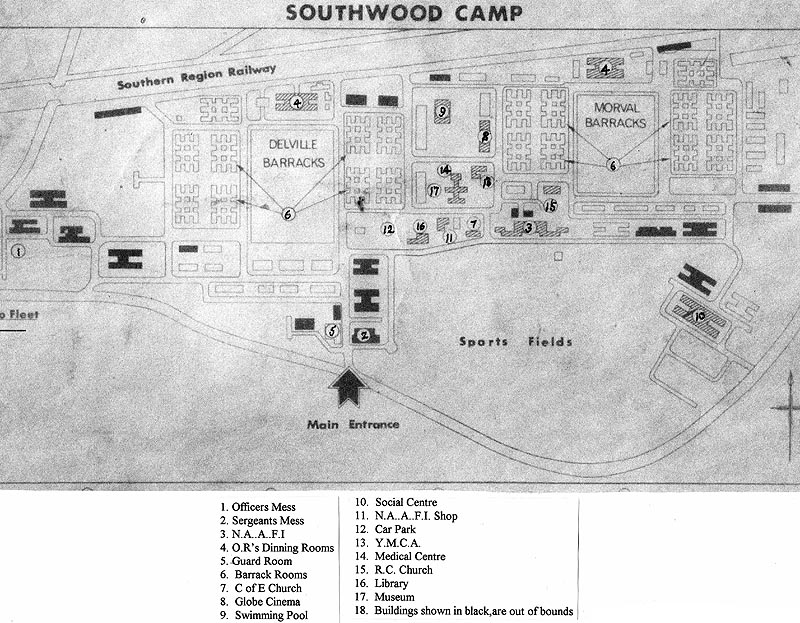

All we raw recruits, speaking with many different accents, from the four corners of the U.K. on arrival at Farnborough station the first morning, were met by shouting N.C.O.s directing us to 3 ton Bedford trucks and T.C.V.s, (Troop Carrying Vehicles,) which transported us to Southwood Camp. There were I think two barracks on this site, called Morval and Delville, and one further down the road called Guillemont. All named after battles fought in France during the W.W.1 Somme offensive in 1916. The buildings, all mainly of wooden clapboard construction, were built, we were told for Canadian troops in W.W.II; there we were installed in huts called 'spiders', (see camp plan) which consisted of a central body or block, which housed the ablutions, lavatories, squadron office and drying room. From this central body were 6 legs or dormitories (I always thought spiders had 8 legs?) and each dormitory (or squad) housed approximately 20 men. A full corporal had a room of his own at the head of each dormitory, and a Lance corporal a bed space next to the exit door. Both these N.C.O's were regulars, so each spider or squadron consisted of approximately 100 plus new raw recruits,('sprogs'and 'nig-nogs'), as we were called by all the N.C.O's., both these slang words having a different connotation today; 12 assorted corporals and lance corporals, one staff sergeant in our case called Abbot ( more of him later,) and a ‘Rupert' O.C (Officer Commanding,) usually a lieutenant.

After sampling the delights ? of army cooking at lunch time, we were marched down to the quartermaster's store to be kitted out with all our clothing and equipment, which also included the Lee Enfield 303 rifle. The one I was given had a nice brass butt plate, and a lovely chestnut colour stock which polished up beautifully, and no doubt contributed to being selected as' stick man,' when at a later date we had to do guard duty. It also had the date of manufacture stamped on the side 1918!

All the webbing equipment had to be blancoed in an pale buff colour, and then left to dry in the drying room. When later I went to collect my neatly blancoed webbing, I found most of it had been stolen, and instead of then taking someone else's, (which I'm told was the thing to do,) I waited until everyone else had claimed theirs and I was left with all the rough remains. Lesson number one, do unto others as you have been done by,--- you live and learn! It was only after this episode that we were given the means to mark ALL our equipment with our own individual army number, and God help you if you ever forgot it! The next visit was to the camp barber where we were literally shorn of all traces of long hair, and to add insult to injury were expected to pay, I think a shilling for the privilege. I don't think I had enough hair to need a comb for the next 6 weeks!

About this time I had a visit from an R.M.P.( Regimental Military Police ) corporal, who had seen the new arrivals, and had taken a fancy to my dark brown sports jacket and fawn trousers, he asked if he could ‘borrow' them for a hot date he had that night. Having been warned what the consequences of a refusal might be, I agreed and earned myself the princely sum of half a crown for my trouble!

This money helped towards the cost of buying all the cleaning equipment we needed, e.g. blanco, brasso, boot polish, and an electric iron, which we had to pay for out of our own money. The brasso as well as being used to burnish one's buttons, badges, and buckles, was also used to polish the galvanized buckets used for cleaning the barrack room, while the broom ‘bumper', and brush handles, together with the trestle table top had to be scraped white with razor blades. Two lines, one floor board width, at the foot of the beds and stretching the whole length of the room, had to be stained with black Kiwi boot polish, and brought up to a mirror like shine by use of the aforementioned ‘bumper' to meet with the corporal in charge of our squad's approval. His name was Cpl Cave, and his favourite saying was he must have everything immaculate!

Next day after a restless night, when a few homesick sobs could be heard in the darkend barrack room, we were wakened at what seemed like the crack of dawn, by an N.C,O. banging a dustbin lid, with a cricket stump, shouting as he did so, “ hands off c***s on socks, stand by your beds”! Then told to wash and shave (everyday), I had only shaved about once or twice a week up to this point. We were then shown how to make our beds, and lay out our equipment army fashion, for each days inspection. Afterwards being marched down to the O.R.(Other Ranks) mess hall for breakfast, with our mess tins (2) mug (1) and eating irons, (incidentally which I still have nearly 60 years later.)

The next item after breakfast and barrack room cleaning, was a mass visit to the medical centre to receive all our jabs which would protect us against everything, from foot and mouth to the dreaded lurgy! We only had one or two who passed out, but most of us had a very aching arm for a couple of days, due to the T.A.B. shick, tetanus, and various other injections we received.

Of the six squads in the full squadron, one was always designated the awkward squad, and was made up of those who couldn't tell their right foot from their left, couldn't shave without cutting themselves to ribbons, or marched like the chocolate soldiers from toy town. One of the latter was a sapper who also had the unfortunate surname of ‘Lillie'! I found myself in this squad because the second best boots I had been issued with, although having the required number of studs in the sole and the horseshoe blakey in the heel ( all highly polished I might add ) I couldn't pull the leather laces tight enough together for the two sides of the boot to meet! All the training corporals took it in turns with each new intake to train the awkward squad. This was of particular satisfaction to Corporal Cave, and all of us when we came second at our basic training passing out parade some 6 weeks later.

Some names I remember from this time were (see photo) Sgt. Abbot of course, Corporals Cave, and ‘Taffy' Smith, who tried to teach us, on recreational training Wednesday afternoons, the ‘dark' arts of Rugby football. Then there was Corporal Death who you can imagine was given many ‘nick' names ranging from black to warmed up!. Sappers Reg Bannocks, Alfie Coombs, Ernie Bradshaw had all attended the London College of Printing with me prior to call-up. Others in our squad were Collins, Clarke, Bluck, Barber, Bennett, Bridges, Bond, Bumstead, and of course sapper Lillie.

Apart from the ‘bulling up' of all equipment, the drills and marching on the parade ground, where every instruction had to be completed by shouting out the numbers in time with the movement, we had our first introduction to firearms, initially on a 022 indoor range, and later on a 25 yard outdoor range using our Lee Enfield 303 rifles. My lasting memory of this was having a nice black eye, caused by not holding the rifle correctly.

The assault course was another part of the basic training to be negotiated, with plenty of mud and barbed wire to catch out the unwary, and ending up with a run through a building full of tear gas, with our respirators on, and then a second run through with them off! which resulted in sore running eyes and dripping noses, much to the amusement of the N.C.O.'s in charge.

The P.T.I. (Physical Training Instructor), N.C.O's were another source of ‘torture' to we poor victimised recruits, as they put us through exhausting exercises, to reach a fitness level which was acceptable to the army. It seemed, without exception, that all P.T.I's had very high squeaky voices, when they were shouting out their orders to us. I suppose this was due to their high state of physical fitness , and not having been trained as the drill N.C.O's were, in projecting their voices. Although we ‘sprogs' could think up more

sinister reasons (which included surgery!) why this was so!

In keeping with Rudyard Kipling's barrack room ballads, there was also at the time, this National Service man's ‘ballad‘, sung to the tune of ‘The Mountain's Of Mourne.'

They say this man's armys a wonderful place

but the organisations a B***** disgrace

Theres Corporals, Lance Corporals, and Staff Sergeants too

with their hands in their pockets and F*** all to do

They stand on the square and they holler and shout

they shout about things they know F*** all about

For all that I've learnt here I might as well be

shovelling up S*** on the isle of Capri.

Part of the training also, included lectures and films on many subjects which varied from things military to things medical, among which were the warnings of V.D. and its consequences, which always seemed to receive a big cheer from the captive audience.

We were also told that the Royal Engineer Regimental tie, (which has a dark blue background, with one broad, and two narrow, diagonal dark red stripes) represents a river and two streams which Sappers often have to bridge.

The spiritual welfare of all new recruits was taken care of by the Army chaplains, who all held the substantive rank of Captain. We attended for an hour each week, a mixed Christian gathering, teaching us a standard for life, and a promise in death. The favourite requested hymn for some reason was always, 'Eternal Father Strong To Save.' The only Sapper in our squadron excused this meeting was a lad of mixed race from Tiger Bay Cardiff, who claimed to be Moslem.

This large camp at Southwood could boast a cinema, also a well equipped N.A.A.F.I. and a (God bless them) ‘Sally Ann' (Salvation Army) canteen where a game of table tennis, darts or billiards could be played for no cost. Money being very tight as I believe a new recruit National Service man's pay at that time was just 28 shillings a week.

After our initial 6 weeks of basic training, square bashing and the like, we were given our first 48 hour leave, most of us like myself who's homes were within an hour or two of Farnborough, were able to return home and show off in our new B.D.(Battle Dress) khaki uniform to our family and friends, and tell of the sadistic N.C.Os who had given we poor ‘sprogs' such hellish times over the last few weeks (while gently swinging the lamp at the same time!) But many of course lived much farther afield, so were stuck in camp for the whole weekend.

So now being considered basic army trained soldiers, we were introduced to the role of sappers, or as some preferred to be called Field Engineers. This was a 16 week course which included such things as Bailey and improvised bridge building, mines and demolitions, watermanship, trenching, barbed wire entanglements, fortifications, knots and lashes, and many other things concerned with what would now I suppose come under the banner of civil or field engineering. The R.E's were responsible for among other things, railways, postal services, dock installations, roads, and map printing. Which is why most of our training group was made up of people who came from these industries. Indeed I met some of the students I knew from the London college of printing.

During the field engineering course, the squadron was taken to Ash ranges, there we lived under canvas for 2 weeks, and fired every day with the 303 Lee Enfields and the Bren light machine gun, over distances from 100 to 400 yards. You also had to take your turn in the butts, to adjust the targets and signal the hits or misses. This was very noisy when thirty or so Brens were firing on fully automatic, and was also somewhat hairy when some bright spark took a dislike to your signalling a miss for him, and gave the ‘strawberry and cream' flag you were signalling with, a burst with his Bren!

The digging of slit trenches and camouflaging of same, also took up some of our time as did the erection with ‘Dannett' wire of huge barbed wire entanglements, which we were then told to find our way through without the aid of wire cutters. I think the highlight of our visit to Ash ranges was the attack by Sergeant Abbot's smelly old bulldog ‘Winston' on one of the corporals. He bit his hand and would not release it, and in the end had to be shot to make him let go.

On our return to Southwood camp we had a short period of general duties while sprucing up the camp for the annual admin inspection by the Engineer General. My squad was given gardening duties, which included hoeing the weeds in a large vegetable patch, and then on another occasion clearing a large area at the corner of our sports field of head high stinging nettles. As this was the height of a very warm summer, we managed to hang this out (skiving it was called) and enjoy a couple of lazy days.

The general officer's inspection came some few days later after some very intense ‘Bulling' of the camp in general, and our barracks and ourselves in particular - yes, we really did paint coal with white-wash!

On the day of this special inspection, all squadrons or ‘spiders' (numbering some 1,000 or so men) directly after an early breakfast were marched on to the parade ground accompanied by R.E. corps band playing the Regimental march ‘Wings' which we were told was in reference to the Royal Engineers being involved in the formation of the Royal Flying Corps, which was later to become the R.A.F.

We were on the parade ground for almost 4 hours on a very warm day, and although our squadron was in shirt sleeve order, and others in P.T. kit, some weren't so lucky and had to parade in F.S.M.O.( Full service marching order.)

After the ‘trauma' of the General's inspection we were given as some sort of a reward, a visit for half a day into the ‘fleshpots' of the nearby garrison town of Aldershot, where we were introduced to the delights of a N.A.A.F.I dance and the acquaintance of a hoard of W.R.A.C's. ( Woman's Royal Army Corps.) Being transported the 5 or 6 miles back to camp in the small hours of Sunday morning in the Bedford 3 toners.

One evening when I had been at Southwood camp for some 2 months or so, I decided to visit an old friend Ernie Barrett, from my civvy streeet youth club, who had been called up in the past 2 weeks, and was installed at Guillemont barracks, which was just a mile along the road. I almost wished I hadn't bothered, as the corporal of the guard stopped me at the gate, and after checking my turnout, and my A.B.64. Parts 1 and 2, had me marching up and down and performing all the drill movements in front of the assembled guard for the next 15 minutes.

As mentioned previously, after the initial 6 weeks of basic training, we began a 16 week course of field engineering, this involved among many other things learning knots and lashes, for use with improvised bridging.( Having been a cub/scout was to prove useful.) Also Bailey bridge building, where we managed to get a commendation for building a double single 30 foot Bailey bridge, over a large gap in record time for a training squad, I think it was under 30 minutes. Just one casualty, a sapper losing the top of his middle finger when a jack collapsed!

The site where all this training took place was an area of around eight acres, quite close to the actual barracks, where we also practised mine laying and detecting, and also the use of explosives for demolition. The 'Sally Ann' tea wagon always turned up for our break at 10 am, and no matter where you were on the site, the tea wagon always seemed to be at the furthest point from us, so it was imperative to get to it as quickly as possible to ensure a longer break, and not have to queue with a 100 or so others! I think I always managed to be in the first half dozen,( being pretty fit in those days.)

One day during training a small group of us were selected under a full corporal to take a small jeep and a couple of collapsible boats down to a fairly fast flowing river, to give a demonstration of watermanship, in transporting said jeep across the river using an improvised raft mounted on the two collapsibles. The demonstration was for a local boys army school, who took cadets from age 14 - 18. I don't think they were very impressed, when our raft with the jeep on board started taking off down stream, which no amount of frantic paddling on our part seemed to adjust it's direction! I am always reminded of this effort when I see the'Dad's Army' episode on T.V. when the colonel on his white charger was floating gently down the river just like our jeep!

Most of the recruits in the squadron were either Postal workers, railway workers, dock workers, miners, printers, civil engineers, or architects and surveyors, as the R.E. covers all these various trades and professions.

So now just halfway through my field engineers course in August 1951 I, together with a couple of others were ordered to make our way to the School of Military Survey (S.M.S) at Hermitage near Newbury, Hants, to join a 16 week course in Lithographic printing, and if successful an 'A' trade rating. (see Part 2)

Denis Carrington. March 2010